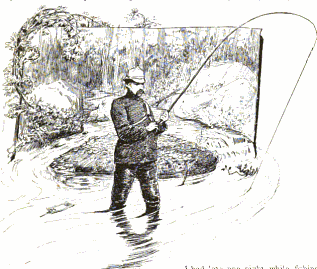

It’s fun to skim through these old books and read how familiar some of this sounds even today. In Outing, Volume 14, which is a collection of essays written in 1889, the pieces cover all kinds of outdoor pastimes. The fishing section of the book starts with a chapter titled, “The Pleasures of Fly Fishing,” by W. Holberton:

“It is generally admitted that every man should have a good, healthy hobby, and if he can ride it out of doors, among the grand old forests or along the sparkling trout streams, so much the better for him. A man without a hobby is a much-to-be-pitied individual.”

From the chapter titled, “American Brook Trout Fishing,” by Charles F. Danforth:

“The Salmo fontinalis, commonly called “brook trout,” is found from Labrador to the Pacific Ocean. Next to the salmon, he is beyond all doubt the greatest favorite of anglers, and fully deserves the praise of all lovers of the rod and reel, his peculiarly delicate flesh, his eagerness to devour—which is so difficult to please— and the mixture of strength, activity and bold courage with which he tries to free himself from the hook when caught, forming a combination of good qualities rarely met with in any other fish.

The brook trout of America is the most beautiful creature in form, color and motion that can be imagined, the handsomest specimen of marine architecture in existence.”

And doesn’t this sound absolutely normal even today?

“Do not be afraid to try new brooks on the ground that you see no trout in them. Trout are seldom seen, and unless one has a rod and line you may walk nearly the whole length of a good stream without discovering any trace of trout within it. Hence comes the usual cry of ” There’s no fish in this brook!” The small brook trout seldom breaks water in running streams: he gives no intimation of his presence, as do the trout of lakes and ponds, and even in these not to any great extent, except at early morning or sunset, and this as a rule only when he has attained a larger size than the fish usually met with in brooks. In order not to be disappointed in this sport, don’t run away with the idea that you are going to get many fish that exceed six or eight inches in length. You can often catch thirty or forty nice six or eight inch trout by following for a couple of miles or so a brook that you can, in its widest part, step across easily; so don’t, I beg of you, despise small brooks.”

And this:

“When you have a bite, do not pull as though you had on a 20-pound codfish, but “strike” your fish, as it is called. This is done by a short, sharp, abrupt inward turn of the wrist. The motion is almost indescribable, but is made by bringing the finger nails of the right hand, which are downward, holding the rod, suddenly to the left and upward, moving the tip end of the pole in the same direction some one or two feet…

Those who pull the instant they have a bite generally see the trout wound around the bushes overhead, or, if he be not hooked, see the line and hook in the same position, causing a loss of time and patience, and, too often, temper. Always bear in mind the fact that trout are very shy, and that, in order to insure success, you must keep perfectly still and out of sight as much as possible, for having once disturbed them it is useless to fish for them in that place. A frightened trout will not bite for you, nor for anyone else, and you must go to the brook very slyly. It makes no odds how good the bait is, they will not bite if they are frightened; so, you see, in order to have much success, you must use some stratagem. In open-meadow fishing crawl up to the edge of the stream and throw the line over carefully, and, if they have not seen you, they will snap at it as quick as a Parker gun lock. Don’t flourish with your rod meanwhile. If they are likely to see you, you had better squat down while you are baiting your hook.”

His opinion is to use bait rather than flies, kind of funny to read and obviously we all prove this incorrect every time we fly fish and catch these little guys:

“To be successful in brook fishing give up almost entirely the idea of using artificial flies. There is hardly any chance to use them, and fish in small brooks seldom take to them. In a majority of them the overgrowth is so thick and heavy that it would be next to impossible to cast a fly, unless in open meadow fishing, and then the average brooks are, in my estimation, so small that it hardly pays for the trouble taken.”

And in many ways, much has changed. This is an account of fishing a tributary of the Lycoming River in Pennsylvania:

“I had late one night while fishing in one of the big pools close under the trees. I happened to look up, and there were two sparks of light, evidently the eyes of some animal staring at me out of the darkness. I kept on fishing awhile, but soon began to feel uncomfortable, and after a bit concluded I did not want any more trout, so quietly backed out and left the pool to the owner of the eyes. Bears, wildcats and rattlesnakes were plenty in that region in those days, and once while driving over to Pleasant Stream we had the pleasure of seeing a fine patither run up the hillside; but these creatures never troubled the angler.”

And just outside of New York City:

“Until within two or three years the wellposted angler could slip down from the city to any of the numerous salt water creeks that empty into the Great South Bay and enjoy excellent trout fishing, but owing to the greed of the trout hogs, who have poached these streams in every conceivable way, they are about used up. How well I remember my first experience in this style of trout fishing. I had always been used to the swift, sparkling mountain brooks, and it did not seem possible that these sluggish and somewhat muddy waters could contain my favorite fish.”

Finally, some prescient words about what the future would hold for our streams and these beautiful fish:

“Scarcely any clear, bright, running brook is without this fish unless for two reasons: first, if it is well known and fished all the time by Tom, Dick and Harry; secondly, if it has a sawmill erected upon it in such a manner that the sawdust flows into the stream, the latter always driving out the trout.”